In conversation with co-curator Catherine Fairbanks about an unwinking practice:

CW:

In curating with you this project, an unwinking practice, communication continues to be a point of consideration in building empathy. For me, this communication involves an exchange as well as a component of trying to hold another perspective, and that more than one truth can exist. What is your understanding of the role of communication with empathy?

CF:

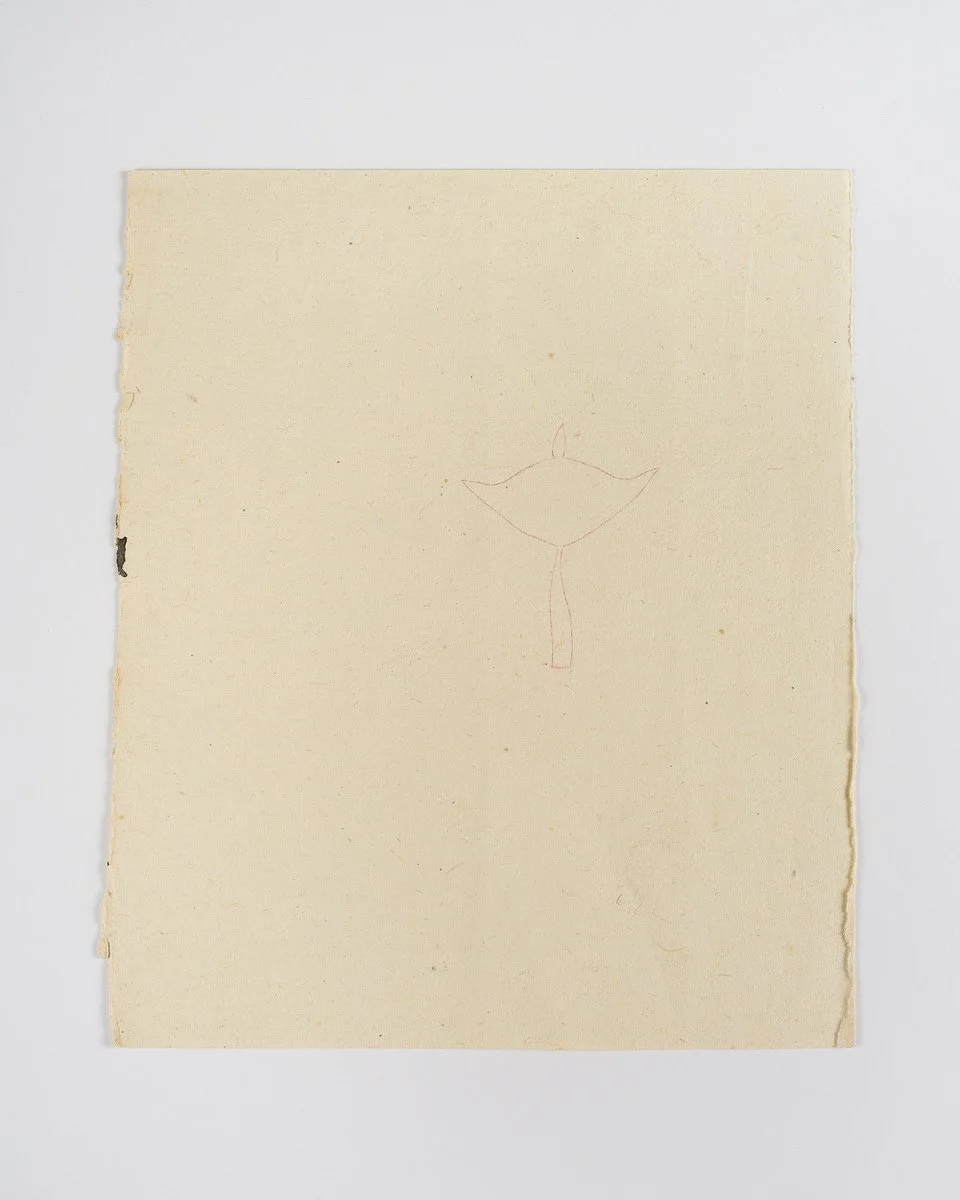

In terms of communication, I trust the work of art, though devious and not conscriptable. I trust the conflict that is present when artists are arriving at themselves and their work. Leonie Guyer writes about her drawings as, “Neither sign nor symbol, while they have a specific character, they invite an open reading. Within the drawing, the shapes are situated with the intention of energizing the whole.” Her works seem to sense their own endangerment and yet do nothing about that threat. The paper is an equal player to the mark, and one only realizes this surprise when, before their eyes, they allow the two of them, the mark and the substrate, to communicate as equals. And similarly, writing by Sarah Workneh also works for me by surprise, and the form of internal-to-itself conflict that her writing often contains. As I start reading her voice, it is surprise she is creating in us. In the letter for this show, I am led by her words past the daily tragedy of roadkill she witnesses and cares for, and then eventually inside the sense of longing for a lost soulmate with whom she built some of her first fleeting attempts at a utopia.

The origin of empathy in German is einfuhlung, a word that has more to do with action and the origin of equality than it does feelings, if you follow the lineage of the phenomenologist Edith Stein. It describes an innate equality, not something we must earn. Edith Stein was killed by the Nazi’s, and her lineage has been lost, I would argue, and one of the motivations for me in this show has been to think about bringing her ideas out of that shadow and examining where we are in the field of art as it relates to empathy. Empathy as equality is an idea that gives me purpose as a nurse, but its role in art is less clear. I recall when we first started talking about making a show about empathy, we were discussing whether it was teachable or not. Could it be taught in schools and institutions, modeled by parents? We questioned empathy’s role, if it even had one, in art (does it?), and its role in society.

CW:

Equality is sadly far from a practiced reality. How do we practice empathy even in places that challenge our beliefs, and by practicing it at all times/during those difficult times, will this strengthen our ties?

CF:

Philosopher/theologian, Rowan Williams, talks about “structural empathy”, that culture should enact structural equality first, and that making a society built on equality is the first step to making a society built on empathy and love. As he interprets Stein, he says it is better to say, when you encounter another human, “I have no idea how you feel” than it is to say “I know how you feel.” The core of Stein’s empathy is infinite difference. We each have an infinite ability to differentiate and express that difference. This is uncomfortable in the dominant culture because of a need to function cohesively; we have wanted to house empathy in similarity, not difference. It is this idea of infinite difference that has caused me to wonder about works of art as a space of empathy and love.

CW:

Does one have to relinquish any idea of control to practice empathy? Empathy as an exchange, the language of offering, asks us to participate- invest in something outside of ourselves. Rachelle Mozman Solano examines the impact of policy on both the individual and the collective. Solano’s work is confrontational in the reconfigured, suggested staged spaces that deconstruct interconnected and bonded histories. Her photographs offer a proposition, allowing for reflection on past roles to find a place within a renewed future. She speaks of “how the soul fits, is lifted up and buried within a present that is acted out, re-staged and reinforced by mythology.”

CF:

Marya Krogstad, in speaking about her work, shares a quote by Mikhail M. Bakhtin in Speech Genres and Other Late Essays; “For one cannot even really see one’s own exterior and comprehend it as a whole, and no mirrors or photographs can help; our real exterior can be seen and understood only by other people, because they are located outside us in space and because they are others. In the realm of culture, outsideness is a most powerful factor in understanding.” This is exciting to me because it is very similar to things that Edith Stein says about seeing ourselves in her dissertation text, On the Problem of Empathy: “As each person requires other people to fulfill their subjectivity, knowledge of the self and others can only be collaborative.”

CW:

Michael Candy’s piece, Persistence of Vision, mines the perception of private and public realms. Previously installed outside, an AI-enabled spotlight disguised as a security camera, “detects the presence of a human and fixes them in its beam with unsettling precision”. Choosing to place Candy’s masquerade CCTV inside the gallery flips his ironic loop again; now viewers are being “spotted” and their attention is illuminated, “amplifying the tension between visibility and control.”

CF:

Dutch anatomist Jaap van der Wal’s idea of the work of the human is the task of building themselves through their entire life, not just in the early years when we typically think of periods of “growth.” Humans are never not building their body, never not constructing themselves, right to the end. Anatomy and form are always actively happening. Maria Walker’s paintings reflect on themselves and their own construction. Maria Walker, on her own art-making process, “It is healing to be seen, plainly and compassionately, without judgment. And inversely, it is healing to be the one who gets to see. When I make my artwork, the interchange is similar. I listen and look. I am rooted in myself while experiencing the object before me. Together we, the painting and I, are present and focused, listening and shifting to one another, stepping forward.”

CW:

In an unwinking practice, the work explores the space where empathy germinates within a private exchange and how that transmutes within a public practice. This circulation- the private to the public, the individual to the collective- generates, as Sarah Workneh writes in her letter, “infinite permutations, and infinite ways to create meaning.”

CF:

For me, empathy is political. Empathy as an action is the realm of Hannah Arendt. Arendt says this is how we resist authoritarian regimes, totalizing captures of power; we choose a life of action. We don’t get to abstract others’ narratives, though our histories are interwoven in time. I cannot think of the political work in this show without focusing on Marya Krogstad’s “Untitled” (TV Fountain). Sitting not far from Michael Candy’s also-aged-out technology, the constant snow on the TV accompanies the ice block as it melts through the slit in the bottom of the rubber-covered chair and into the bucket on the ground. The ice, prepared daily in a small, provided freezer and placed over the slit, cut to just allow its volume to melt into the bucket in 24 hours, upon which the scene is replayed. As Maria Walker’s paintings are a diagram of building and reflecting, Krogstad’s is loss under scored circumstances: scripted care work, gravity and the bedpan, the aged TV, the melting body.

CW:

Sarah Workneh, in her piece, (grass covers me), the sharing of a personal letter, unearths the intersection and wovenness of private and public places. She writes, “Maybe I am worried about naming things I don’t want to think about or giving shape to things I don't really want to recognize.” By approaching the practice of empathy as circular and continuous, we get a chance to practice again and again, and somehow, maybe we get a glimpse into the cycle of death within life. Sarah Workneh writes to her friend and to us, “This letter is an ouroboros, the never-ending cycle of death and life; the toggle between present pressures and future futures; the slippage between you and me. Not an anticipation of the end, but a return to the beginning.”

Sarah Workneh’s (grass covers me)